The United States government’s top leaders have painted a rosy picture of the manufacturing industry, with President Donald Trump crediting an uptick in domestic factory work to companies bringing their operations back to American soil.

The industry indeed enjoyed an increase of 284,000 jobs in 2018, according to federal labor statistics. The numbers are still nowhere near pre-recession levels, but the increase last year was the largest since 2009, according to an analysis by the Washington Post. So far, the U.S. has gained back 1.4 million of the 5.8 million jobs lost from 2000 to 2010. Up to 40 percent of added jobs in 2018 can be attributed to operations returning from abroad, the Washington Post reported, citing The Reshoring Group, which focuses on bringing manufacturing jobs back to the U.S.

[Above: Greenville Technical College students work with equipment in the Center for Manufacturing Innovation]

Trump’s business-friendly tax policies can be credited with the increase, though the job gains began in President Barack Obama’s administration. But as with most large-scale economic trends, no single president can take full credit for improvements. Even more, it’s difficult to tell if these returned jobs are here to stay or if they’re just a blip.

Manufacturing workers continue to face competition from robots and still-strong globalization trends that lure companies to countries where labor is cheaper. Federal training and apprenticeship programs are still lacking, too, as the Trump administration attempts to defund an Obama-era public-private partnership program.

What’s certain is the manufacturing jobs that have returned are different from those in an industrial past. While the “dirty jobs” are still there, the necessary skills have shifted away from the baby boomers’ talents toward operating and maintaining automated robotics-centered equipment.

What’s certain is the manufacturing jobs that have returned are different from those in an industrial past. While the “dirty jobs” are still there, the necessary skills have shifted away from the baby boomers’ talents toward operating and maintaining automated robotics-centered equipment.

Tech and community colleges are filling the resulting skills gap in the workforce by offering training in advanced technology studies, such as computerized circuitry for automotive production. When those jobs change again, as they certainly will, the colleges will be there to retrain workers.

Few communities have witnessed the evolution in manufacturing more than Greenville, S.C., home to Greenville Technical College (Greenville Tech). The city enjoyed a thriving textile trade until the 1960s, when the factories began to move abroad. Those jobs never returned, but local and state governments made aggressive moves to bring new industries to the area, says Jermaine Whirl, vice president of Learning and Workforce Development at Greenville Tech.

One of those efforts was establishing the college in 1962. Ten years later, French tire manufacturer Michelin opened a factory in Greenville. In 1992, German automobile company BMW opened a plant there. The same workers who had previously produced textiles were now making tires and luxury vehicles using the same skills they had used before.

Roughly 45 people move to Greenville County every day to join the ranks in the advanced manufacturing sector, which now includes companies such as GE and 3M in addition to Michelin, BMW, and roughly 700 other manufacturers employing 500,000 people.

“I can’t produce enough graduates to keep up with what they’re asking me to produce,” Whirl says. “The environment for advanced manufacturing is robust.”

Manufacturers in the region ship their products internationally, so there is some uncertainty about how the Trump administration’s tariffs and global trade will affect the cost of doing business, Whirl says. South Carolina’s port at Charleston is one of the busiest in the country for sending goods overseas.

Regardless, companies still seek to expand their operations in Greenville County and will adjust their business models according to changes in tariffs, Whirl says. There’s no shortage of interest in our manufacturing education programs, he adds.

“There’s nothing wrong with a four-year degree, but there is a lot of power when it comes to community colleges offering localized workforce training built with industry in the room,” Whirl says. “These are sustainable wages and go up from there, … which is tremendous given they’re coming out with little debt.”

Changing Outdated Perceptions

Colleges and manufacturers alike still struggle to change the perception of the manufacturing industry. Schools are trying to educate students and parents that the days when factories were hot and loud are over, says Doran Moreland, executive director of diversity and inclusion at Ivy Tech Community College of Indiana.

“It is an eternal struggle to try to get people to stay up to date on what the actual manufacturing space looks like today,” Moreland says. “Even our lawmakers still likely think of a place that’s noisy and dirty and dusty where people are banging with hammers all day. … But it’s actually more likely a super mechanized environment with clean rooms and people in white uniforms working around robots.”

Dmitry Kopytin was one of those people who had that old mindset. “I never saw myself in manufacturing,” says Kopytin, 35, a supervisor for an apprenticeship program at BMW. He was working in construction to support his wife and two young boys when the housing crisis hit.

Kopytin decided to go to Greenville Tech for a certificate in mechatronics, an interdisciplinary manufacturing branch that combines electronics and mechanical engineering. When people ask him what he does, he tells them, “I’m a robot doctor. When equipment breaks, they call us and we fix it.” He earned two more certificates and then a two-year degree, ultimately landing a mechatronics job at BMW.

“I laid a foundation of my education, the pillars. Now, I have to work on the roof. Once you get your base set, now you’re tweaking and finagling what your skills are,” Kopytin says. “You’re constantly trying to polish your skills because technology is constantly changing.”

Greenville Tech built a 100,000 square-foot manufacturing innovation center in part to train students but also to further change the perception of the industry. The Center for Manufacturing Innovation is a place where student technicians can work alongside engineering students from nearby Clemson University to collaborate on ideas and problem solving.

K-12 students go on field trips there to learn about advanced manufacturing. They can interact with robots, 3D printers, and other technology to discover what manufacturing is, Whirl says. Reaching out to youth is doubly important, he adds, because the industry’s workforce is aging.

“We need to start working with the first grader now to expose them to the industry,” Whirl says. “We have our fair share of an aging population [whose retirement] in the next decade will be a critical concern for us. So we’re trying to gear up now.”

“We need to start working with the first grader now to expose them to the industry,” Whirl says. “We have our fair share of an aging population [whose retirement] in the next decade will be a critical concern for us. So we’re trying to gear up now.”

Responding to a Rapidly Shifting Industry

Colleges respond to the growth in advanced manufacturing by providing short-term degrees or certificates specifically tailored to meet employers’ needs and to accommodate students’ personal lives. That approach gets an unemployed worker back on the job quickly. From there, they can work their way up, says Michael Hoffman, executive director of continuing education at Des Moines Area Community College (DMACC).

“Flexibility is key in being able to build and adjust based on what businesses need,” says Kay Maher, a workforce employment training specialist at DMACC. “It’s an opportunity to provide another option to higher education. That two-year or four-year path just does not fit for everybody.”

DMACC, Ivy Tech, and Greenville Tech all offer flexible and constantly evolving programs to meet companies’ needs.

To guide its curricula, Ivy Tech focuses on key economic sectors in Indiana, including advanced manufacturing, logistics and supply, information technology, healthcare, agriculture, and construction. Using federal labor statistics, the college “triangulates with employers” to determine what training needs to be offered, Moreland says.

Short, eight-week courses provide condensed, accessible learning and allow job seekers to quickly adapt to companies when their needs change. A student might complete a certification that provides a basic knowledge of electronics and then continue to build on those skills with the support of their employer.

“We would love to have students here full-time, but the reality is we have to meet students where they are,” Moreland says.

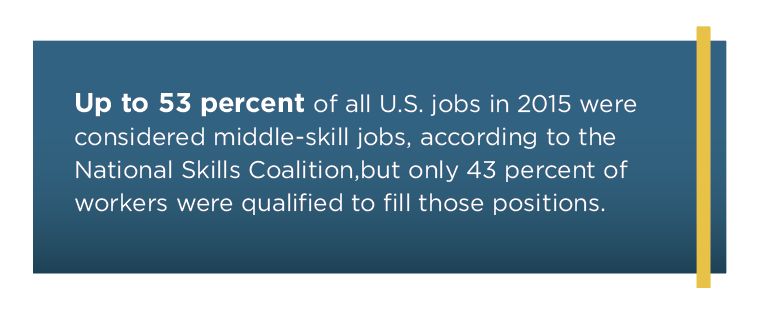

Ivy Tech also focuses on developing the “middle-skill space,” says Chris Lowery, senior vice president for workforce development at Ivy Tech. “[Employers] don’t have problems attracting people with bachelor’s and master’s degrees,” Lowery says. “It’s that middle-skill space that’s really squeezing us.”

Middle-skilled workers might have a high school diploma but less than a four-year degree, Lowery says. “What we’re talking about is a gateway to the middle class. These are really well-paying jobs most of which have great benefits.”

Short-term programs can quickly provide the skills workers need to begin their careers. These shorter programs provide a diploma or certificate that proves their value, Lowery says.

In Greenville County, a local economic development employee for the Greenville Area Development Corporation works full-time solely as an industry manager. The manager’s job is to touch base with every company annually to see what issues they need solved, be they policy- or workforce-related. “She does a thorough analysis of what they need and how the county can assist them,” Whirl says, helping keep Greenville Tech up to date on the skills its students need.

Who Pays for Worker Retraining?

Kimberly Garcia benefitted from a short-term welding program at DMACC. She completed her certificate within four months and went from earning $11 an hour at a job with no promise of advancement to earning $15 an hour with growth opportunities at a welding shop in Des Moines.

“I don’t want this to be just another job. This is my career, and this is my life,” Garcia says. “You’re never too old to start living your life.”

Regardless of how motivated Garcia was, it would have been difficult for her to afford tuition while simultaneously paying child support for her three children. Fortunately, Iowa legislators created two continuing funding packages in recent years to provide tuition assistance and other support services to students in need of training and employment.

DMACC receives $300,000 annually from the state for tuition assistance in diploma programs and $800,000 annually to pay for staff and assistance to students who are 250 percent below the poverty line and underemployed or unemployed.

Without wraparound services such as providing gas money, Hoffman says, life circumstances might prevent workers from pursuing better careers at all. In addition to giving the financial support, the state-funded Pathways for Advancing Careers and Education (PACE) program pays for “Pathway navigators,” employees who act almost as a type of social worker to make sure student needs are met.

Without wraparound services such as providing gas money, Hoffman says, life circumstances might prevent workers from pursuing better careers at all. In addition to giving the financial support, the state-funded Pathways for Advancing Careers and Education (PACE) program pays for “Pathway navigators,” employees who act almost as a type of social worker to make sure student needs are met.

“We want to make sure students don’t drop out because they don’t have gas to get to class,” Maher says. “[The Pathway navigators] become that point of contact for the students.”

At Greenville Tech, students benefit from company-sponsored apprenticeship programs to pay for tuition. South Carolina also has a lottery system that covers half of tuition costs for students in high-demand career paths.

BMW’s apprenticeship program, called BMW Scholars, supported 200 participants in 2018. Students attend class full-time and work part-time at the BMW plant. The company pays $1,500 toward tuition and books at four area technical and community colleges, provides healthcare benefits, and pays students for their work at the plant. Another business in the area, eye health products company Bausch and Lomb, covers full tuition, books, and fees if students agree to work for them after graduating.

“We really pride ourselves on being a community that wants to do advanced manufacturing,” Whirl says. “It really does take the private, public, and education [sectors] coming together.”

Kelsey Landis is the editor-in-chief of INSIGHT Into Diversity. This article ran in our May 2019 issue.