Veterinary technicians (VTs) play an essential role in veterinary medicine.

They are often called upon to complete the tasks that a veterinarian isn’t required by law to execute, including filling prescriptions, giving injections and vaccines, and performing CPR.

Credentialed veterinary technicians report high levels of burnout due to a combination of stress, compassion fatigue, low pay, and having to compete for jobs with individuals who have not earned an associate or bachelor’s degree in the field, according to Kenichiro Yagi, who worked as a veterinary technician for over two decades before becoming a VT educator. He currently serves as the manager of the Veterinary Education Simulation Laboratory at Cornell University and is co-chair of the Veterinary Nurse Initiative (VNI).

The VNI, formed in 2016 and based on research conducted by the National Association of Veterinary Technicians in America (NAVTA), is an effort to improve professional standards, public and professional recognition, and career potential for veterinary technicians. For example, the VNI is advocating for a national standardized education process for all veterinary technicians rather than the current state-by-state approach that requires varied levels of training depending on where a VT lives.

The VNI, formed in 2016 and based on research conducted by the National Association of Veterinary Technicians in America (NAVTA), is an effort to improve professional standards, public and professional recognition, and career potential for veterinary technicians. For example, the VNI is advocating for a national standardized education process for all veterinary technicians rather than the current state-by-state approach that requires varied levels of training depending on where a VT lives.

[Above: Veterinary nurse Dru Mellon in front of the Utah State Capitol in February 2020. Mellon successfully campaigned for veterinary technician credentialing to be required by state law.]

When it comes to professional recognition, VNI leaders hope that changing the occupational title from “technician” to “nurse” will better convey the essential role these workers play. Similar to nurses who provide healthcare services to humans, veterinary technicians “do a lot of the client communication,” Yagi says. “We may be the person who first sees the client and patient and takes the [medical] history.”

When it comes to professional recognition, VNI leaders hope that changing the occupational title from “technician” to “nurse” will better convey the essential role these workers play. Similar to nurses who provide healthcare services to humans, veterinary technicians “do a lot of the client communication,” Yagi says. “We may be the person who first sees the client and patient and takes the [medical] history.”

They are often the ones responsible for explaining medications, procedures, and other aspects of animal care to clients, according to Yagi, who notes that veterinary technicians are typically able to do so in “less jargon-y” terms than a veterinarian. Many of their other responsibilities are comparable to the tasks that nurses in human settings complete, including listening to the heart and lungs, taking temperatures, and attending to patients in surgery.

The ultimate goal of gaining recognition for this work and elevating the professional status of VTs is to reduce turnover and address the shortage in the profession — one that the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projected would grow by 17,900 jobs between 2014 and 2024.

The ultimate goal of gaining recognition for this work and elevating the professional status of VTs is to reduce turnover and address the shortage in the profession — one that the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projected would grow by 17,900 jobs between 2014 and 2024.

The shortage is “a bit of a chicken or the egg problem,” says Yagi. “We’re having a hard time finding [qualified] technicians because they’re leaving the field, not feeling fulfilled, or being under-utilized.”

The shortage is the main reason clinics hire non-credentialed individuals to serve as veterinary technicians, Yagi says. Credentialed VTs earn either an associate or bachelor’s degree in veterinary technology or nursing and have to pass a state exam. Allowing people without these qualifications to carry out the responsibilities of a veterinary technician creates a consumer protection issue by potentially endangering animals, according to Yagi. Furthermore, having to compete for jobs and salaries with untrained individuals leads to frustration, burnout, and turnover among actual VTs.

The shortage is the main reason clinics hire non-credentialed individuals to serve as veterinary technicians, Yagi says. Credentialed VTs earn either an associate or bachelor’s degree in veterinary technology or nursing and have to pass a state exam. Allowing people without these qualifications to carry out the responsibilities of a veterinary technician creates a consumer protection issue by potentially endangering animals, according to Yagi. Furthermore, having to compete for jobs and salaries with untrained individuals leads to frustration, burnout, and turnover among actual VTs.

Schools of veterinary medicine can help address such problems by teaching a “team structure” whereby veterinarians recognize the qualifications VTs have obtained and trust them to perform their roles effectively, says Yagi.

“If we can create a culture where veterinarians are able to focus on what they went to school for — diagnosis, prognosis, prescribing treatment, and performing surgery — and are utilizing the technicians in a more expansive manner, that is something we should really shift toward,” he says.

Another way veterinary nurse advocates are trying to improve workforce recruitment and retention is by raising awareness of state title protection laws, which specify the qualifications needed to hold a specific occupational title.

NAVTA recently issued a survey examining how well VTs across the country understand these laws in their state, how important they view such laws to be, and what they know about enforcing title protection.

NAVTA recently issued a survey examining how well VTs across the country understand these laws in their state, how important they view such laws to be, and what they know about enforcing title protection.

“What we hear from members of our profession is that even though many states have title protection laws [for VTs and veterinary nurses], they’re just not being followed,” Yagi says. “We often hear that people are afraid of retaliation from their work if they report an individual who is non-credentialed.”

Despite these challenges, both individual veterinary technicians and institutions of higher education are engaged in their own efforts to elevate the profession.

conference in July 2019.

Dru Mellon, for example, is a veterinary technician who serves as secretary of the Utah Society of Veterinary Technicians and Assistants (USVTA). He led efforts between USVTA and the Utah Veterinary Medical Association to change the fact that theirs was the only state that did not require credentialing of any kind for VTs.

On March 25, 2020, Utah passed legislation supporting VT state licensure.

“It’s my hope the legislation helps advance the profession. The goal is to help increase the training and education of people working in the field so that people remain longer in the profession,” Mellon says.

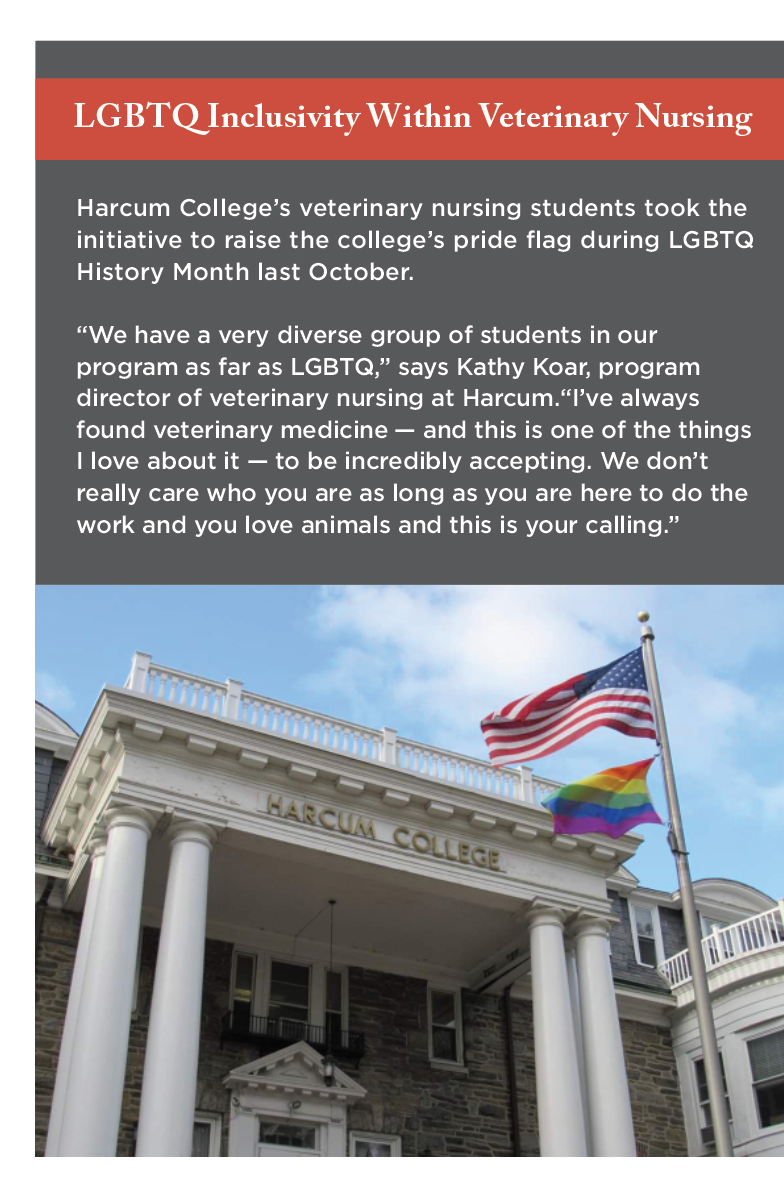

Meanwhile, Harcum College in Pennsylvania recently became one of only six institutions in the U.S. to change the name of their veterinary technology program to veterinary nursing. The college admitted its first class of veterinary nurses in January 2019, according to program director Kathy Koar.

Meanwhile, Harcum College in Pennsylvania recently became one of only six institutions in the U.S. to change the name of their veterinary technology program to veterinary nursing. The college admitted its first class of veterinary nurses in January 2019, according to program director Kathy Koar.

Koar views program name changes such as this to be an important step that colleges and universities can take in support of the VNI, which she says has “come along at the right time in the history of our profession.”

“[The initiative] addresses a lot of the problems veterinary nurses struggle with on a day-to-day basis, like lack of public awareness of what we do, low salaries, not being able to advance within our jobs, and for that reason, moving from job to job and not staying in one place,” Koar says.

Yagi, whose career has included multiple certifications, a master’s degree in veterinary science, myriad public speaking opportunities, and now leadership roles within higher education, says he doesn’t want to be the exception when it comes to the career potential of those in veterinary nursing.

Yagi, whose career has included multiple certifications, a master’s degree in veterinary science, myriad public speaking opportunities, and now leadership roles within higher education, says he doesn’t want to be the exception when it comes to the career potential of those in veterinary nursing.

“Many veterinary technicians have the opportunity to do some of these things,” he says. “They just don’t realize it because their environment isn’t necessarily encouraging them.”

Ginger O’Donnell is the assistant editor of INSIGHT Into Diversity. This article ran in the May/June 2020 issue.